Science or Sensation?

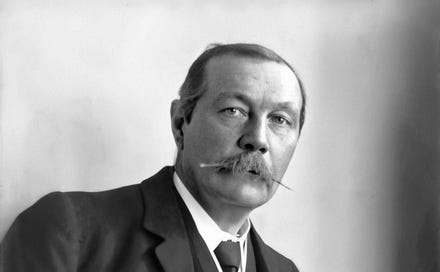

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The devoted spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle shows his narrator, Dr. Watson, beginning a long association with Sherlock Holmes in pursuing a mystery: The mystery Watson himself pursued was Sherlock Holmes. In the beginning, Watson was too delicate to inquire directly into his new roommate’s life. He was simply trying to figure him out, and had no idea that Sherlock Holmes was in the midst of developing forensic standards and applications for criminology.

Every story, of any kind, includes the mysterious—what the reader does not, at first, know. Things for them to puzzle over much as Watson tries to figure out Sherlock Holmes. A condition of subliminal suspense is evoked in a reader by the pen of a writer. It need not be breathless suspense (I prefer not), but it must be of a kind to interest readers without them quite being aware of it.

Not only scene by scene. Sentence by sentence, even word by word, a reader is drawn with quiet unsuspected miniscule threads of curiosity. Wind these invisible filaments about the reader’s imagination, spider-like, layer on layer—and what begins as a single tenuous thread, easily snapped, becomes inescapable interest: A reader enmeshed.

One of the categories on Watson’s list of clues to Sherlock Holmes was Holmes’ extreme interest in “agony” columns and the sensational press of his day, the late 19th century. Because he did not yet know Holmes well, Watson found this peculiar. Studying the history of this canon at Signum University, students may find that this firm believer in the supernatural—the credulous Conan Doyle himself—seems peculiarly at odds with his artistry for scientific analysis. Just so, Watson’s observation did not seem to accord with his new roommate’s arcane and at times rather dry studies. Sherlock Holmes had a profound knowledge of chemistry and could recognize soil types at a glance. He had written a monograph on how to distinguish between 140 types of tobacco ash. Watson threw his self-composed and fruitless list of clues about Holmes into the fire. He was not going to understand Sherlock Holmes this way.

The enthusiastic Dr. Amy Sturgis, in teaching her course on Sherlock Holmes, made us aware of the extent to which the sensational press of that so progressive century devoured popular attention. It reached across class. Royalty as well as the tradesman interested themselves in the yellow press; professionals, aristocrats and gentry; any child who could read devoured what was in the press: both the agony columns and sensational fiction serials such as ‘The Woman in White’ and ‘The Moonstone’ by Wilkie Collins: All were captivated. And yet, to Watson, it seemed extraordinary that this analytical, logical thinker, this man among books, test tubes and Bunsen burners, could care for the sensational press. However, if he—as chronicler—does his job right, Sherlock Holmes will unfold both for Watson and his readers as he writes. Part of that chronicling is the inclusion of his initial failure with that list of clues.

(Science or Sensation?—more to come)

© S. Dorman 2024